THE CHURCH OF NICAEA – part 1

The bishops who gathered at Nicaea under the chairmanship of the emperor Constantine in 325 belonged to a very different church from the one we are familiar with today. This article explores some of the differences.

Constantine had probably only been convinced of the reality of Christ in 313, at the battle of Milvian Bridge. This was when he became the emperor of the Western Roman Empire. He then made Christianity a legal religion.

But he then found the empire becoming convulsed in controversy. A priest of Alexandria in Egypt, Arius, had popularised ideas in opposition to the city’s bishop. His memorable phrase, “There was when He was not”, became widely popular and controversial. (The phrase signified that the Son of God or Word of God was not eternal like God. Instead he was the first act of God through whom God created the universe). Constantine’s reaction was, “When all this subtle wrangling of yours is over questions of little or no significance, why worry about harmonising your views? Why not instead consign your differences to the secret custody of your own minds and thoughts?” Reported in Eusebius, Life of Constantine 2.71)

Why not indeed? The answer lay in the previous two hundred and fifty years of the church’s existence. This can be summed up under three headings: a question of truth; the reality of evil, and the self-understanding of the Christian community.

1 A QUESTION OF TRUTH

Spirit/Flesh

Paul describes precisely the problem facing the first, and subsequent, followers of Jesus. ‘We proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles’ (1 Corinthians 1.23). And not just the crucifixion. Paul addressed the Areopagus in Athens, and was given a good hearing while he talked about the one invisible creator God. But he lost his audience when he spoke of the coming judgment and Jesus being raised from the dead. ‘Now when they heard about the resurrection of the dead, some began to scoff…’ (Acts 17.32)

What was the problem? For Paul as a Jew, we are a unity of body, soul and spirit. But the Graeco-Roman world took it for granted, following Plato, that it is the spirit that is us, and the body is just the envelope. So the very physicality of the crucifixion was religiously shocking. And a for suffering – surely the spirit is immune from suffering, just as God is ‘impassible’, i.e.cannot suffer.

Paul preaching in Athens by Raphael 1511

So what was the answer? Surely it was the spirit of Christ which brought salvation to the world. The body of the earthly Jesus could by definition contribute nothing. By the end of the first century the small conventicles of Christians were shaken by having in their midst people with just such views.

‘Many deceivers have gone out into the world, men who will not acknowledge the coming of Jesus Chris in the flesh; such a one is the deceiver and the antichrist.’ (2 John v.8)

Around 110 Bishop Ignatius, on the way to his martyrdom in Rome, wrote his letter to the Trallians. Some godless men assert that He suffered in phantom only.’

The destruction of the Temple and the Demiurge

The Menorah of the Jerusalem Temple carried by victorious Roman soldiers, Arch of Titius.

By the mid-2nd century there were a wide variety of these super-spiritual sects. What they had in common was a profound pessimism about the physical universe. This may have developed because of the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. It had been the focal point of Jewish worship for over a thousand years. Many Jews became utterly disillusioned with their religion and sought refuge in the new Christian groups. Such sects proliferated on the edges of the Christian communities. They asserted that beneath the one supreme God was an evil or stupid creator god called the Demiurge or Craftsman who made the mess we are in. The only hope was a purely spiritual being who could guide his followers with the correct passwords. These would lead them through the multiple stages leading to final liberation. This movement is called gnosticism, from the Greek word for knowledge.

In the second century a gnostic Christian from Alexandria, Basilides, commented on the belief that Christ suffered and died. “The man who believes that is still a slave.” In fact, he asserted, that Christ exchanged his body with that of an unwitting passerby: “And Jesus stood laughing, as the man, through ignorance and error, was crucified in his place.”

How to respond?

How could faithful Christians respond to such slanders? The first line of defence was contact with those who had actually known Jesus during his earthly ministry:

‘That which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon n touched with our hands, concerning the word of life … (1 John 1.1)

Or Paul: ‘Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen the Lord?’ (1 Corinthians 9.1)

As the first apostle died out, they installed leaders who could affirm at second hand the truth of the Christian message.

Papias, c. 130, wrote, ‘If anyone chanced to come who had actually been a follower of the elders, I would ensure as to the discourses of the elders, what Andrew o thwart Peter said, o what Philip, to what Thomas or James, or what John or Matthew or any other of the Lord’s disciples; and the things which Aristion and John the elder, disciples of the Lord, say…’

The witness of baptism

For well over two hundreds years every single Christian had been immersed in water during the night before Easter Day. (The Didache specified that if there was no running water available, the water should be cold). Each had personally declared their faith in the one threefold God – the Father, the Son who in Jesus died and rose again, and in the Holy Spirit. Creeds developed not as tests of orthodoxy but as summaries of faith taught to new Christians by the local bishop. But it was not enough in the face of the subtle attacks made by the little antichrists who ‘went out from us but they did not belong to us’. (1 John 2.19) While some of the original witnesses remained alive, the reality of Jesus life, ministry, death and resurrection could be vouched for. When the last had died, what then?

Enter the New Testament

Reliance on the memory of the original apostles was a diminishing asset. Once no church leader had contact with someone who had actually known Jesus, there needed to be some other authoritative witness. Different churches probably had their own particular gospel: Alexandria had Mark, Antioch Matthew, Ephesus John, Rome Luke. It seems that the bulk of the New Testament was accepted throughout the church by around 180. That was when Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons (c.130 – 200) wrote his book ‘Against the Heresies’. In it he gives final authority to the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

At about the same time an unknown Christian wrote a statement on what books should be taken as authoritative. These were the four gospels, including Luke and John, thirteen letters of Paul, the letters of Jude and John, and the Apocalypse of John and of Peter – though the last was doubtful. It is called the Muratorian Canon after the Italian cleric who discovered it in a Milan library and published it in 1740. The ancient writer of the fragment mentions the popular Christian book ‘The Shepherd of Hermes’ but says it should not be included the canon. The reason was it was ‘written quite lately in our times by Hermas while his brother Pius, the bishop, was sitting on the chair of the church of the city of Rome.’ Pius I died in 155.

So, just as the local bishop provided the authority in matters of faith and worship, so now the Bible became the testing ground for any new interpretation of the Christian faith. The Gnostics produced their own gospels, but none of them are earlier than the second century and are pretty weird reading.

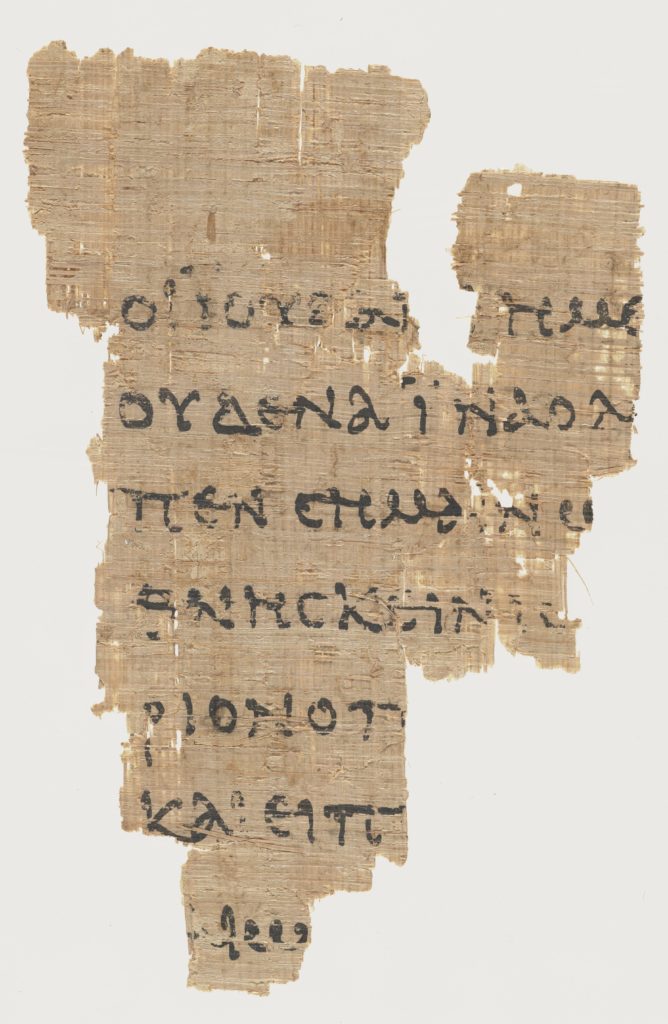

The oldest fragment of a gospel,John 19 c.125 CE

Standing firm

In the second century the Church had survived by standing firm against the blandishments of the super-spiritual Gnostics. Standing firm became Christian bishops’ second nature. It was a natural reaction, summarised by a graffiti I saw in the monastic territory of Mount Athos in Greece: ‘Orthodoxy or death!’

2 DEMONS AND HELL

Exorcisms

Right at the start of Mark’s gospel, right after Jesus’ baptism and his call of the first disciples, comes the story of Jesus’ first acts of power:

‘When the sabbath came, he entered the synagogue and taught. They were astounded at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes. Just then there was in their synagogue a man with an unclean spirit,and he cried out, ‘What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God.’But Jesus rebuked him, saying, ‘Be silent, and come out of him!’ And the unclean spirit, throwing him into convulsions and crying with a loud voice, came out of him. They were all amazed, and they kept on asking one another, “What is this? A new teaching—with authority! He commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.”’ (Mark 1.21-27)

It is not a passage which most clergy feel comfortable in preaching on. Bu for the early church, it was pure gold. The ancient world was consumed with a fear of demonic forces. The celebrated German theologian Harnack wrote: ‘The whole world and its enveloping atmosphere was filled with devils; not merely idolatry but every phase and form of life was ruled by them. They sat on thrones, they hovered around cradles.’

The Pharisees practised exorcism, but according to a story in Acts not always successfully, see Acts 19.13-17. On the other hand, when seventy of Jesus’ disciples went on a preaching and healing tour, on their return they reported jubilantly. “Lord, in your name even the demons submit to us!” (Luke 10.17). The fact that sufferers from parasitic spiritual forces were delivered and healed was undeniable even by such a convinced opponent of Christianity as the philosopher Celsus. He wrote a powerful attack on the Christian gospel around 175 called ‘The Word of Truth’.. But even he could not deny the efficacy of Christian exorcism; he ascribed it to Christians’ practice of magic. This is what the Jerusalem scribes said about Jesus. ‘“He has Beelzebul, and by the ruler of the demons he casts out demons.” (Mark 3.22)

To come up to date, here is a report from a 2025 newsletter from the Bible Society. Madame Teteh, a French teacher, leads the Open the Book Bible sessions in a school in Banjul, the capital of Gambia. ‘Florence, a 12 year old, whispered to me outside her school, “I was walking home one day when I heard a voice of something like a devil. It was telling me I need to kill someone.” With tears running down her cheeks, she told me, “It made me very scared…. I asked Madame Teteh if she could pray for me , and after she did, I never heard that voice again. I’m free and I’m not afraid.”’

Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, writing around the same time as Celsus, said, ‘Those who are in truth Christ’s disciples, receiving grace from him, do in his name perform miracles… Some do really and truly cast our demons, with the result that those who have been cleansed from evil spirits do frequently believe in Christ and join themselves to the Church.’

Modern icon of Irenaeus

And then there was hell

I once skim-read the New Testament to see if I could find any teaching about hell as a place of eternal torment. To my surprise I barely found any. There was the parable of the rich and an Lazarus (Luke 16.19-31), but even Revelation talked about the lake of fire as the second death – which could just as easily mean extinction rather than torment.

It was only in the second centur the church started to consign people to everlasting torture. Polycarp, on his condemnation as a Christian in 155, responded to the governor’s sentence in these words. “You threaten me with a fire that burns for a season, and after a little while is quenched; but you are ignorant of the fire of everlasting punishment that is prepared for the wicked.”

Fifty years later Tertullian, a theologian, gloated. “What sight shall wake my wonder, what my laughter, my joy and exultation? As I see those kings, those great kings … groaning in the depths of darkness! And the magistrates who persecuted the name of Jesus, liquefying in fiercer flames than the ones they kindled against the Christians!”

By 400 a popular book, the Apocalypse of Paul, described hell as full of Christians who had not come up to scratch. Christians who left church services to engage in idle disputes would stand in a river of boiling fire up to their knees. Slanderers of other Christians would be in it up to their lips. Theologians who failed to teach that Christ had come in the flesh or that the bread and wine of communion were the body and blood of Christ were enclosed in a deep well with an unbearable stench etc. Hell by Fra Angelic c. 1431

Whose side are you on?

The bishops who gathered at Nicaea were not Oxbridge dons, they were fully engaged in the lives of the Christians in their citoes. They knew that spiritual warfare was really going on, and that the outcome for themselves and others was a blessed or dreadful eternal future. They held in their hands the present and eternal fate of themselves and of their congregations.

Compromise was not the name of the game.

NEXT MONTH

THE CHURCH OF NICAEA – part 2

ONE HOLY CATHOLIC …

The self-understanding of the Christian community.

0 Comments