Ten days ago Linda and I were having a lovely weekend in East Kent. We discovered the enchanting church of St Leonard in the tiny village of Baadlesmere. I picked up the Parish Magazine and found an article by ‘Diane’ which is the best exploration of how to talk about God that I have encountered. It’s just what I started revandybook.org for. Other websites are seenandunseen.com and the Thinking Faith Project at www.princeodoemena.com. Happily, she agreed that I could share it with you. Here it is. My only contributions are the sub-headings and the images, because for me text without pictures is like a day without sunshine.

Andy

THINKING ABOUT GOD

The Difficulty

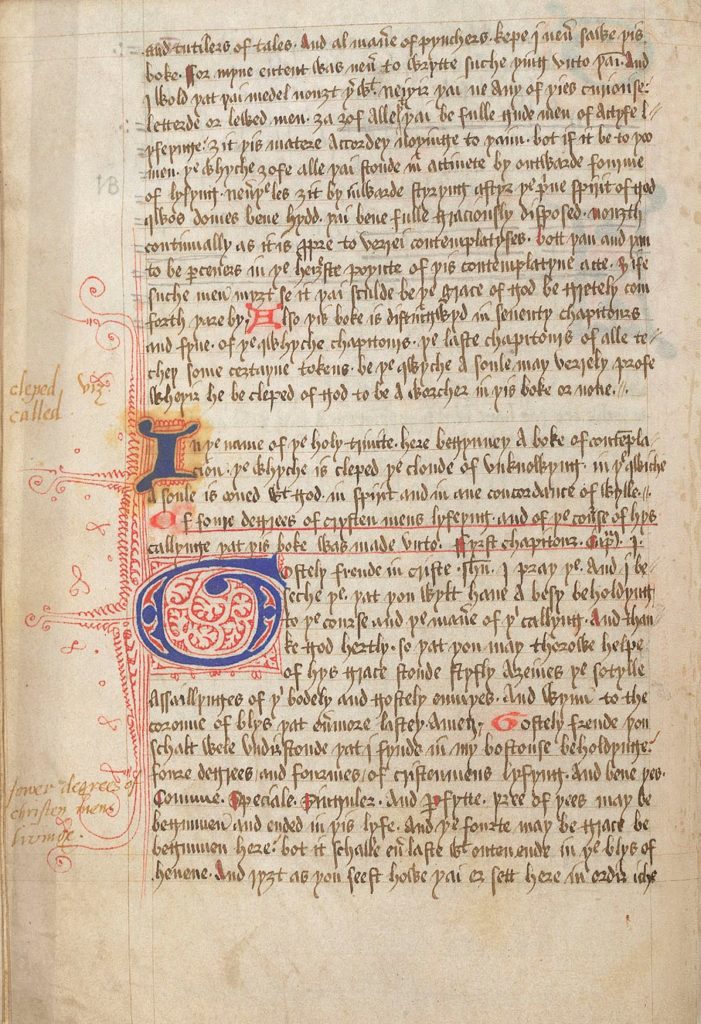

I have been pondering the great difficulty which we have in thinking about God, who is, by definition, the creator of human beings, and therefore immeasurably greater than human beings can understand. “By love he can be grasped and held, but by thought neither grasped nor held” says the author of “The Cloud of Unknowing”, the Canterbury Cathedral Lent study book. The Bible doesn’t really help us: the vision of God in the first chapter of the book of Ezekiel is confusing and utterly unimaginable, while Moses is told, “You cannot see my face for man shall not see me and live” (Exodus 33, 20). And yet some of us (vicars included) persist in talking as if God is somehow like a person somewhere “out there”, and as if we know exactly who “he” is and what “he” is up to. It is hardly surprising that so many people cannot believe in that sort of God.

Page 1 of the Cloud of Unknowing, 15th century

Paul in Athens

I think St Paul, talking in Athens to the Greek philosophers (Acts 17, 24-28), whose business it was to think, is far more helpful. He had noticed a statue “To an unknown God”, and observed: “The God who made the world and everything in it…does not live in shrines made by human beings, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all human beings life and breath and everything.” He reminds his listeners of words written by two of their own poets: “In him we live and move and have our being.” It is as if God is the element in which we naturally live, just as fish live in water.

No Coward Soul

It is the saints and the poets who best speak to us of God. Here is Emily Bronte, in her poem, “No Coward Soul”, written probably three years before she died from tuberculosis in 1848:

- No coward soul is mine

No trembler in the world’s storm-troubled sphere

I see Heaven’s glories shine

And Faith shines equal arming me from Fear.

2. O God within my breast

Almighty ever-present Deity

Life, that in me hast rest,

As I Undying Life, have power in Thee.

3. Vain are the thousand creeds

That move men’s hearts, unutterably vain,

Worthless as withered weeds

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main.

4. To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by thy infinity,

So surely anchored on

The steadfast rock of Immortality.

5. With wide-embracing love

Thy spirit animates eternal years

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates and rears.

6. Though earth and moon were gone

And suns and universes ceased to be

And Thou wert left alone

Every Existence would exist in thee.

7. There is not room for Death

Nor atom that his might could render void

Since thou art Being and Breath

And what thou art may never be destroyed.

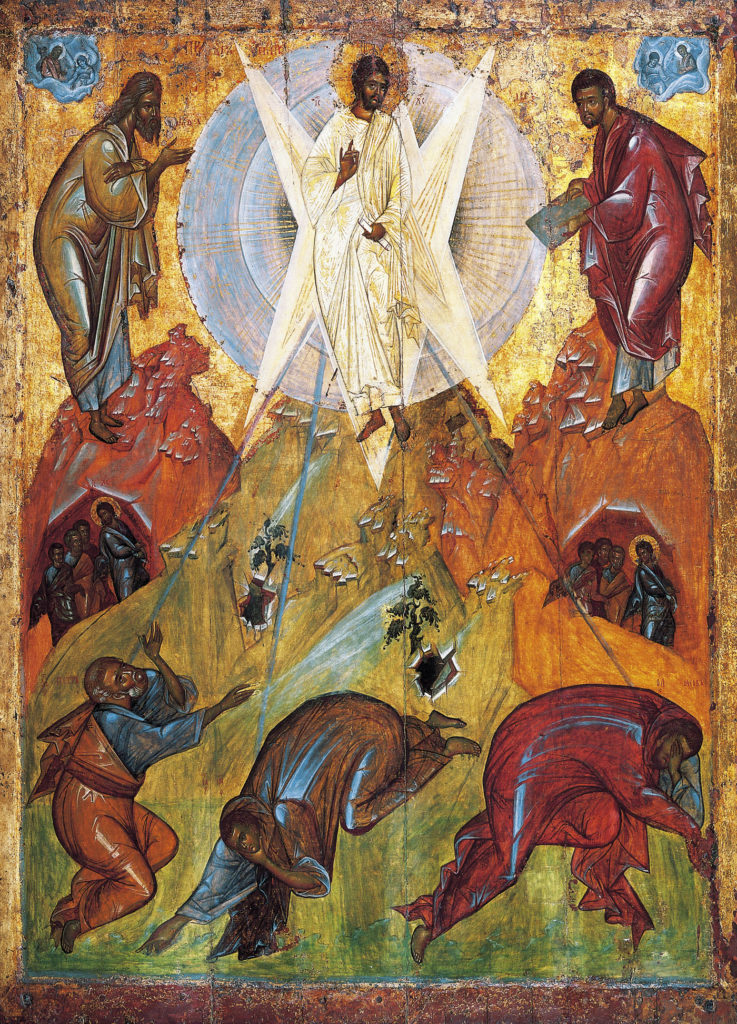

The Force of Life

The poem is a triumphant declaration of faith in a powerful God, who is the force of Life, the life of the Universe, and beyond the Universe, of which the speaker in the poem, whom I take to be Emily herself, is a part. “God within my breast”, in the second stanza of the poem, is the God spoken of by the anchoress Julian of Norwich in the fourteenth century, who said “We are all in Him enclosed, and He is enclosed in us… He sitteth in our soul.” If we speak of God we usually say “he” because of the limits of language – but Julian and Emily know that God is Spirit, neither a “he” nor a “she” but the “Thou” of Emily’s poem – the One who calls us into relationship. We are, each of us, in relationship with God, whether or not we are aware of this. Jesus spoke of God as his father, “I and my Father are one” (John 10, 30), and taught his disciples to pray to God as “Our Father” (Matthew 6, 9), which suggests that we are, every one of us, beloved children of God.

(Note: Photo by Andre Moura)

Wide-embracing love

The poem states that all the beliefs about God, all that we think or try to say about God, are like “withered weeds” with no roots or fruits, or like so much froth, without substance, compared with the “rock” which is the infinite, and ungraspable “wide-embracing love” of the Divine Energy as it goes about the processes of creation. John’s first letter (4,16) says, “God is Love, and whoever lives in love lives in God, and God lives in that person”. We see that love revealed in the record of the life of Jesus of Nazareth given to us in the gospels. We, too, are meant to be lovers: loving God with our hearts, minds, and souls, and being channels of love for our world (Matthew 22,37).

Divine Energy

The sixth stanza says that we are all connected in the Divine Energy which gives birth to, and is omnipresent in, but not coterminous with, the whole creation. Because we have separate bodies we believe that we are wholly separate beings, but the truth is that we are part of the web of creation, and part of other beings (animal, vegetable and mineral!) across time and space, and also part of God’s being since every existence exists in God. God is beyond human conception of time: in eternity, all is present. The final stanza declares that “There is not room for Death” because God is Being itself, and cannot be destroyed. The writer of the letter to the Colossians understands that Christians have symbolically died through their baptism , and their “lives are hidden with Christ in God” (3,3). But, as we have seen, the poem suggests that all lives are hidden in God.

A Choice

It seems that we have a choice: we can believe that the Universe occurred by a chance conglomeration of chemicals or atomic activity, and is ultimately meaningless; or we can accept the mystery of “the Love that moves the sun and other stars” (God in Dante’s Paradiso, Canto 33,145), or, as in the original, “l’amor che move il sole e l’altre stelle.”

0 Comments