BUDDHA & CHRIST

Reflections at the V & A

The V & A

The Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington is one of the great museums of the world. After visiting it regularly for years, I still discover new galleries. Whether it’s fashion, high art, history, amazing craftsmanship or the latest in digital design, the V&A has it for you. In particular it is an arena where two of the major world faiths display their most characteristic features. Most Buddhist images portray serenity. Christian images portray emotions and even agony. Is there any meeting ground between these two faiths or are they just polar opposites??

The First Galleries – Buddhism

If you enter at the original main entrance in Cromwell Road, go past the information desk and turn right or left, you are among many Asian statues of Buddha. All the faces are calm and half smiling. Serenity is the name the game.

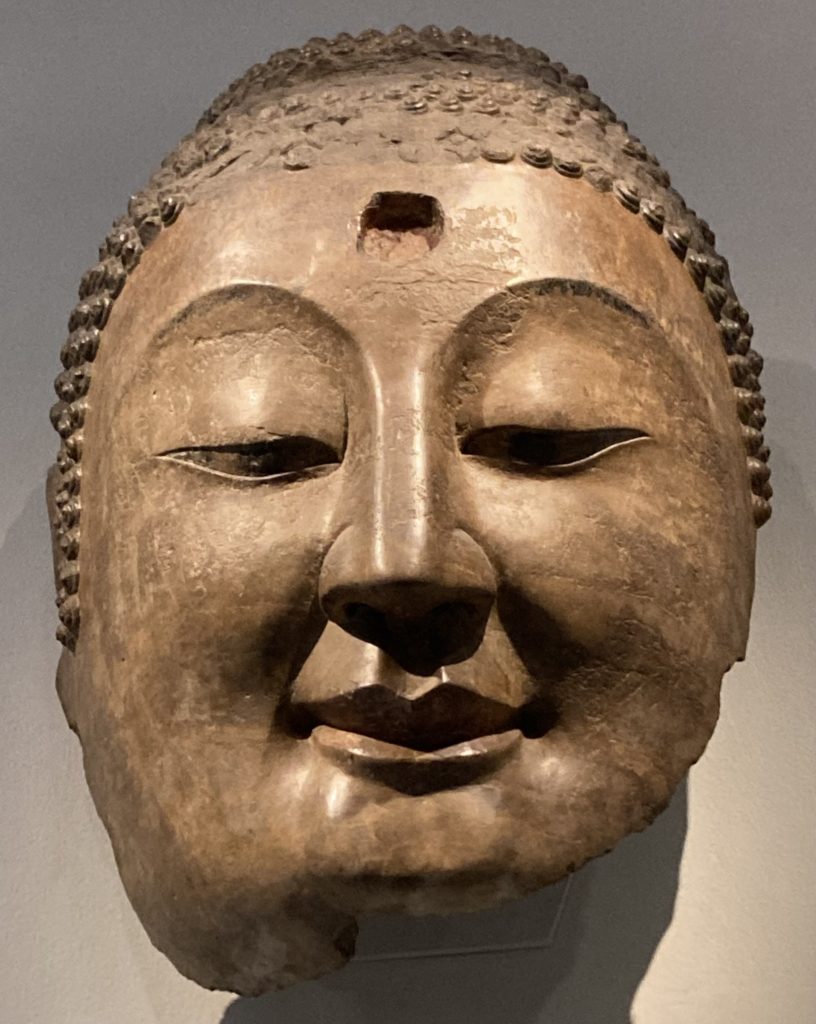

This gigantic head was once part of a gigantic statue, c. 550, in northern China

The statue left is from Thailand,1868-1910.

It portrays a different story, from before Siddhartha Gautama was awakened. It shows an emaciated seeker putting himself through extraordinary ascetic practices trying to attain nirvana. Eventually he realised that such effort was not the way, and he eventually attained buddhahood while sitting quietly under a bodhi tree. ‘Buddha’ means ‘awakened’.

He then began preaching that there was a way to end our experience of suffering and dis-ease, and that way was for each individual to attain. As he said to a devotee: “It is not my practice to free anyone from confusion. When you yourself have understood the Dhamma, the Truth, then you will find freedom.”

Or as the Zen saying puts it more bluntly, “If you meet the Buddha, kill the Buddha.” More prosaically, there is no authority to appeal to beyond yourself.

Buddhism describes itself as ‘the Middle Way’. “There is a middle way between either following, or struggling to repress harmful thoughts that arise. I learned that, through meditation, I can simply bear witness to them, and allow them to pass on according to their nature. I don’t need to identify with them in any way at all.”

(Sister Ajahn Candasir, ‘Jesus in the World’s Faiths’ p.24)

The above describes well the Theravada tradition of Buddhism, as practised particularly in Sri Lanka and South-East Asia. It holds closely to Buddha’s original teaching in the 5th century BCE. The key practice is Vipassana meditation in which one simply observes one’s passing thoughts and lets them go. It is widely practised in the West under the name ‘mindfulness’.

The Mediaeval Galleries

If you enter by the Cromwell Road entrance, turn immediately right and go downstairs you find yourself in the Middle Ages. Ever since the conversion of Constantine in 315, the Christian story has provided the iconography through which Western Christendom interpreted itself.

At first Christ was shown simply as a young man as in this fourth century mosaic. Then he was shown as the majestic ruler of all, and the judge at the Last Judgment

In the Cast Courts is a Victorian renovated cast of Christ as judge, from the 12th century church of Shobdon, Herefordshire.

From mediaeval times, however, the Christian emphasis was on suffering and emotion. The key image was of Christ nailed to the cross. At first the figure portrayed stoicism and a sense that Christ himself willed it, like a soldier embracing battle. A small 10th – 11th century reliquary shows this.

From the 12th century onwards Christians portrayed the suffering of the cross more and more graphically. The body of Jesus becomes twisted in agony in an appeal to move the hearts of those who see it, as in the life-size 14th century crucifix right.

A classic example of this is a story I heard of an Archbishop of Paris who was killed in the 19th century. As a teenager, he was part of a gang of tearaway young men. One evening he accepted a dare to make a spoof confession to a priest. He went in to the confessional and made a ridiculous confession, trying to hide his giggles. At the end the priest said, “I will absolve you, if you go and stand in front of the crucifix over the altar and say, ‘All this you did to me, and I don’t give a damn.’ “ He tried to say the words but broke down in tears and his life was converted.

Or as St Paul said in Galatians 2.20: ‘I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.’

The apex of emotion in Christian art is the suffering, death and burial of Christ

Left is the Italian terracotta group ‘The Lamentation over the Dead Christ’, workshop of Andrea della Robbia, 1510-1515.

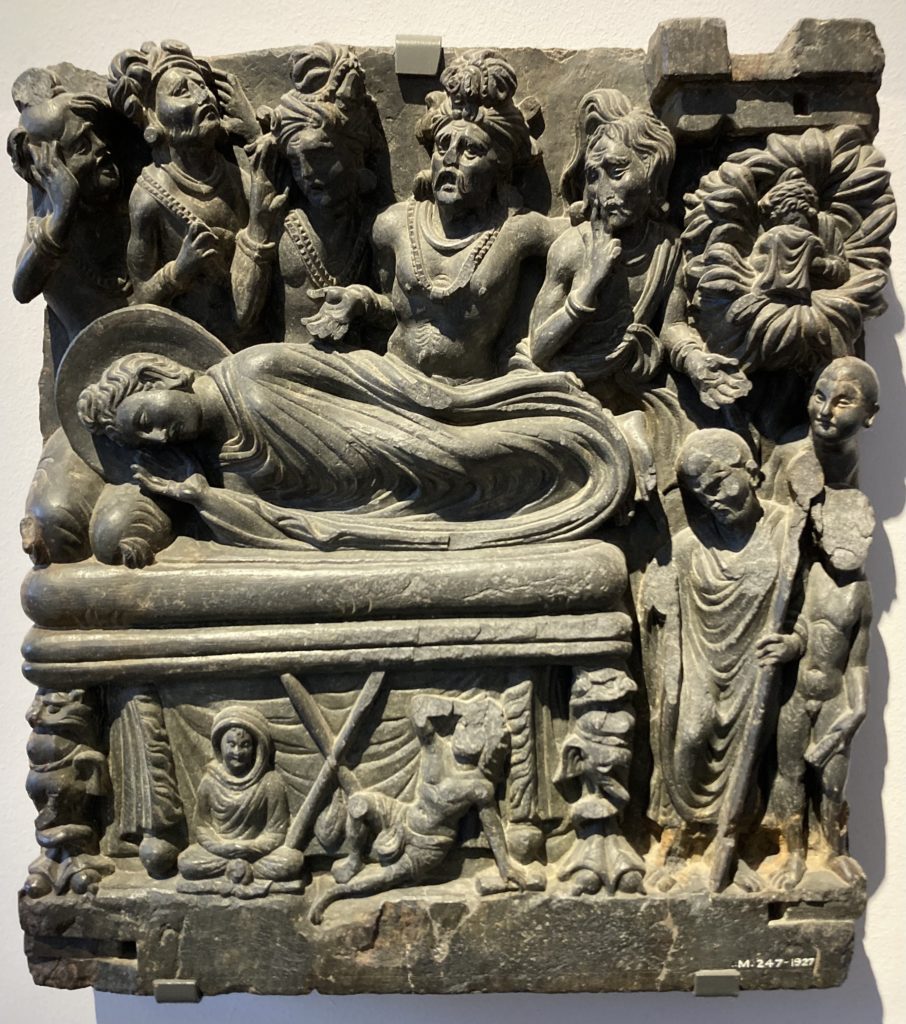

There are similar scenes in Buddhist art, with princes grieving at the death of Buddha, or rather his final release from the cycle of rebirth. The real point of it is the small figure at the bottom left. He is Subhadra, a recent convert to the Buddha’s teaching, sitting quietly, meditating.

The Death of Buddha, 100-200 CE, ancient Gandhara

Monkey and Cat

In the Hindu tradition there are two different types of religion, the monkey and the cat. ‘Sabio Lantz’ in his website ‘Triangulations’ described them as follows:

‘Have you ever seen a baby cat carried by its mother? What does the kitten do? The kitten does nothing — it just submissively hangs there in surrender while the mother carries it all around. Thus in cat religions, the believer is dependent upon the god for salvation and for grace.

‘On the other hand, imagine how a mother monkey carries her baby — she doesn’t! The mother monkey actually barely pays attention to the baby monkey. The baby monkey must hold on for dear life. Thus in monkey religions, salvation is made by the effort of the believer. The god (here the monkey) is available for sustenance while not even being aware of the believer — this god is not personal and is a source of strength and love that only is available by participation of the individual.’

So is Buddhism simply a monkey religion and Christianity solely a cat religion? Or is there something more to say?

The New Entrance – Buddhism Galleries

If you go in through the brand new entrance in Princes Gate, you come straight in to the Buddhism galleries, right and left. They tell how Buddhism developed and changed through centuries.

About two thousand years ago the concept of the bodhisattva developed, someone who seeks enlightenment not for himself but out of compassion for other beings. This is the foundation of Mahayana Buddhism. Boddhisatvas were usually shown wearing the robes and jewellery of Indian royalty to express their inner grace and compassion.

The figure above left is of the Bodhisatva Maitreya, meaning loving-kindness. He is at present in heaven, waiting to become the next Buddha on earth.

Later Vajrayanic or Tantric Buddhism promoted a practice of saying mantras and imagining deities during meditation to acquire the gods’ spiritual properties. The hope was that they could attain enlightenment within a single lifetime, rather than through many lifetimes as in the earlier tradition.

The statue shown right is of the goddess Tara (1100-1200)who is worshipped for her protective powers and compassion.

The Pure Land is the name for the aura of spiritual enlightenment which surrounds buddhas, those who are awakened. The Western Pure Land was created by Dharmakara Bodhisvata in primordial times five aeons ago as a state to which all could aspire, principally by reciting the Name. The figure to the left is of Amida Buddha (1200-1300)

The Japanese teacher Shinran (1173-1263) taught that the Amithaba Buddha, or Amida Buddha, does not merely reside in the Pure Land but is ever present in the world as the spiritual potential in all beings to attain Buddhahood. Enlightenment is attained when the Buddha’s mind is manifested in the heart-mind of the devotee.

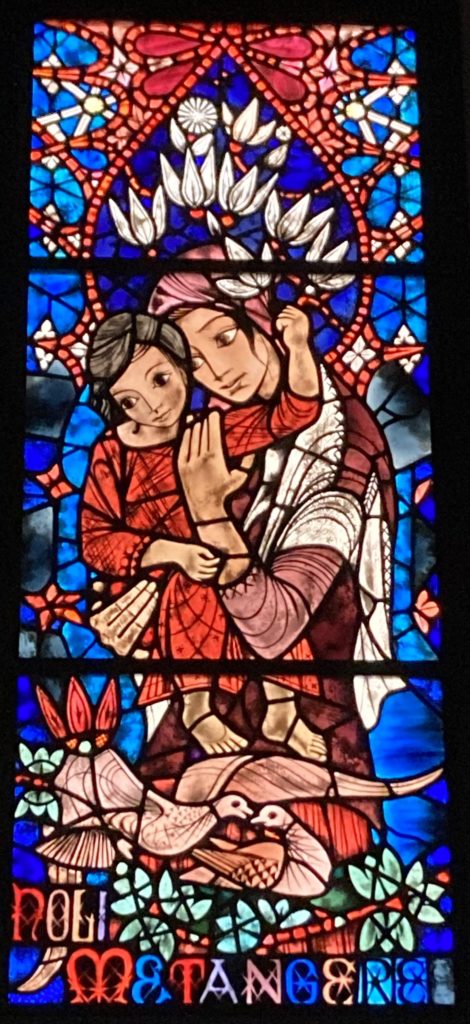

Because the key virtue of the bodhisatva is compassion, the image of Christ that particularly resonates with Mahayana Buddhists is the image of the Virgin and Child.

Buddhists in the Mahayana tradition can revere Jesus as an inspiring and effective boddhisatva, who, like other bodhisattvas, has opened the way of compassion to all.

A modern stained glass representation of Jesus and Mary, done by the Hungarian artist Bossanyi as a memorial to his mother.

Meditation/Contemplation

‘Too many notes, dear Mozart, too many notes’ is what Emperor Joseph II supposedly said after the first performance of the ‘Entführung aus dem Serail’. There is a time when the religious seeker says ‘Too many words, my dear teacher, too many words.’ The novelist E M Forster made the cutting remark, ‘Poor, talkative, little Christianity.’ The same could well be said of the complex philosophical models of Buddhism. But there is a way through!

Buddhist Silence The way of silence in Buddhist meditation is well-known, and indeed is seen as the particular mark of Buddhism. This may be through paying attention to one specific physical sensation or to one’s breathing. In Vipassana meditation one simply notes the thoughts that come into the mind and lets them pass on until a state of quiet is reached. This is the root of the practice of mindfulness which was originally introduced to the west as a method of pain relief.

There is also the Indian practice of using mantras as a way of stilling the mind, popularised here by the Beatles in the 1960’s.

The Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita 6.19 sums it up: ‘Just as a lamp in a windless place does not flicker, so the disciplined mind of a yogi remains steady in meditation on the Supreme.’ (Viveka Vani)

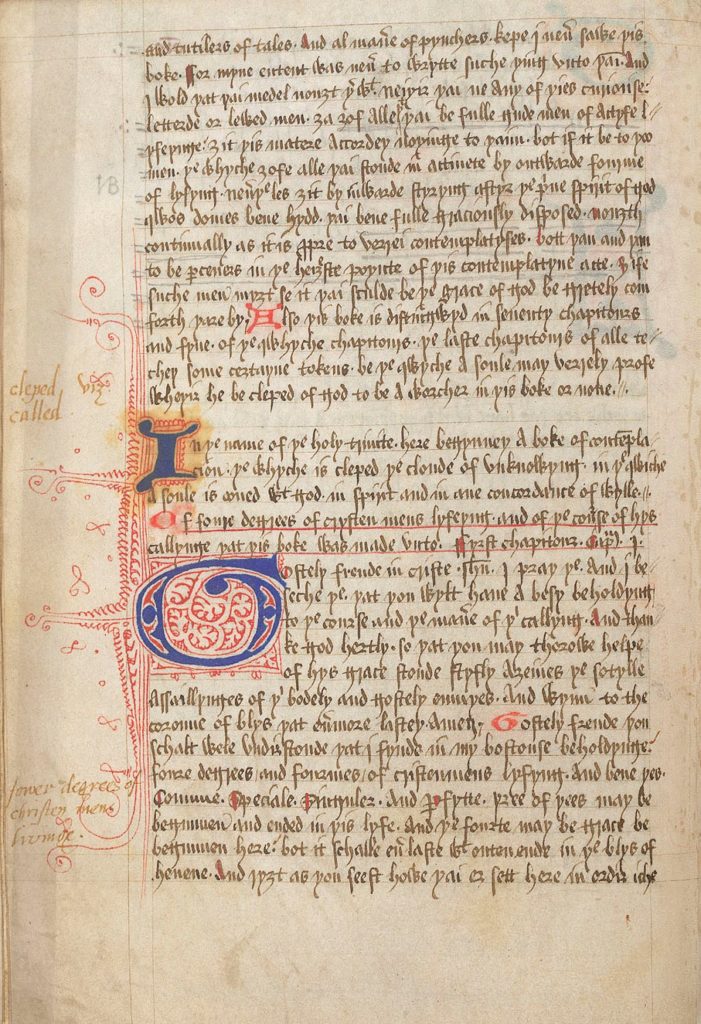

Christian Silence At least by the 4th century, Christians were practising the prayer of silence. They used mantras like ‘Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner’, or ‘O God make speed to save us, O Lord, make haste to help us.’ (Psalm 40.13). Monks both in the east and west sought to encounter God through prayer. Meditation meant active mental engagement with scripture. Contemplation meant turning away from conscious thought and seeking a direct spiritual vision. This is what an anonymous Northamptonshire priest in the 14th century called ‘the dark cloud of unknowing’.

The Reformation in the 16th century made Protestant churches suspicious of anything that was not directly sourced in the Bible under the slogan ‘sola scriptura’ – ‘scripture alone’. In modern times many churches have rediscovered the value of Christian meditation or centring prayer.

First page of ‘The Cloud of Unknowing, 15th c manuscript

The practice is described by Fr Basil Pennington:

1 Sit comfortably with your eyes closed, relax, and quiet yourself.

2 Choose a sacred word that supports your intention to be in the Lord’s presence.

3 Let that word be gently present as a symbol of your intention. 4 Whenever you become aware of anything (thoughts, feelings, images etc.), simply return to your sacred word, your anchor.

Silent Together

The Dalai Lama wrote that ‘in a discussion … on contemplative prayer, I was impressed by striking similarities not only of experience, but even of the language used to evoke it.’ He found that ‘discussion between sincere practitioners of Christianity and Buddhism can be mutually enriching and spiritually sustaining for both parties.’ (Towards a True Kinship of Faiths, pp. 73, 71)

A Good Place

The Victoria and Albert is a museum, not a place of worship. But all one needs to practice meditation or contemplation is quiet spot. And the V&A does have such a place. It is the Chapel of Santa Chiara (Saint Clare) in the Renaissance gallery. You go into the main entrance at Cromwell Road, take the first main turning the right, walk to the end and there it is.

The Santa Chiara chapel is the only Italian Renaissance chapel you can see outside Italy. It was built between 1490 and 1500 and has a slightly earlier altar and tabernacle. It exudes a sense of peace, order and beauty. Very helpfully there is a handsome wooden bench right in front of it, ideal for meditation.

The short poem by St John of the Cross (1542-1591) is an ideal accompaniment. It is called ‘Suma de la Perfection’, ‘Summary of Perfection’:

Olvido de lo criado Memoria de al Criador Attention de la interior Y estarse, amando del Amado

or, in English,

Forgetting what is created, Remembering the Creator, Focussing within, And stay there, loving the Beloved.

A Conclusion

In general interfaith events are events where nothing is said that some present might find uncomfortable. The result is something peaceful but boring. Multifaith events embrace the specifics of each religion even when they are contentious. The result is something much more interesting. I am a firm supporter of the latter. You only need curiosity and respect. With these two attitudes, life becomes an endless adventure!

_______________________________________________________________________________

For further reading: Centering Prayer – Basil Pennington

The Dhammapada

Jesus in the World’s Faiths – ed. Gregory Barker

Towards a True Kinship of Faiths – H.E. the Dalai Lama

0 Comments